Associate Professor Amanda Fitzgerald, of UCD School of Psychology in University College Dublin, on what supports and challenges young people’s mental health in the community? The My World Survey 2 — a large national study of youth mental health in Ireland

In Ireland, a third of the population is under the age of 25 years (Central Statistics Office, 2016). Internationally, we know that 75 per cent of mental disorders begin before the age of 25 years (Kessler et al., 2007). Despite youth being a critical time of vulnerability, many young people do not get adequate support at this time (Patel et al., 2007). For example, in a European study with 30,532 adolescents aged 14-17 years, among those who reported deliberate self-harm (DSH) in the year prior to the study (n=1,660), nearly half (48%) had not received any help following DSH and those who received no help were found to be heavily burdened (Ystgaard et al., 2008).

Mental health conditions can influence young people’s social, emotional and cognitive development, their educational attainment and their potential to live a healthy and productive life. In addition, poor mental health is strongly related to other health concerns in young people, such as substance abuse and poor sexual health (Patel et al., 2007).

To adequately and effectively address mental health problems, there is a need to understand all facets of youth mental health; the protective and risk factors. In addition, there is need to know more about how young people seek help, if one wishes to improve the quality and outcomes of mental healthcare. For health professionals, knowing the factors that can influence the mental health of young patients, having an ability to make a contextual assessment of mental health, and being able to identify significant mental distress, places them in the ideal position to provide proactive, youth friendly care (Mitchell et al., 2017).

Present article’s focus

Present article’s focus

The current article will highlight two key findings from the My World Survey 2 (MWS-2) of relevance to health professionals, notably, 1) help-seeking patterns in youth and 2) key risk and protective factors, with a focus on lifestyle factors related to young people’s mental health. In the paper, adolescents are referred to as those from 12-19 years of age in second-level education and young adults are referred to as those aged 18-25 years post-second level education.

Methodology

MWS-2 focuses on both the risk factors associated with mental health distress and the protective factors that can support young people’s mental health. Nearly 10,500 adolescents aged 12-19 years from 83 second-level schools, randomly selected from the Department of Education and Skills database participated in MWS-2 Second Level (MWS-2-SL). Data collection in schools took place between October 2018 and May 2019.

For the MWS-2 Post-Second Level (MWS-2-PSL), 7,897 young adults aged 18-25 years from Irish universities and institutes of technology, and who were employed participated. Of the MWS-2-PSL sample, 69 per cent were female. A number of standardised scales were used to assess both positive and negative domains of mental health.

Two mental health outcomes of interest in the MWS-2 included anxiety and depression. Anxiety in the MWS-2 was measured using the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) Anxiety subscale which assesses core features of anxiety such as autonomic arousal, skeletal muscle effects, and situational anxiety.

Depression was measured using the DASS-21 Depression subscale which assesses hopelessness, lack of interest, anhedonia, dysphoria and self-deprecation (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). Using recommended cut-off scores on the DASS-21, participants can be classified into normal, mild, moderate, severe and very severe levels of depression and anxiety.

The first MWS study took place in 2012 with over 14,000 young people aged 12-25 years, see full report at www.myworldsurvey.ie.

Trends

The proportion of adolescents reporting severe anxiety has increased twofold from 11 per cent (in MWS-1, Dooley & Fitzgerald, 2012) to 22 per cent (in MWS-2). Levels of severe anxiety in young adults have increased from 11 per cent in MWS-1 to 26 per cent in MWS-2. There was also an increase in the proportion of adolescents who reported severe depression from 8 per cent in MWS-1 to 15 per cent in MWS-2. A similar pattern was found for young adults, with an increase in depression from 14 per cent in MWS-1 to 21 per cent in MWS-2.

Despite an increase in anxiety and depression, there was an increase in some protective factors, particularly in relation to family support and support from a significant adult. Adolescents in MWS-2 were more likely to report the presence of one good adult in their lives (76% in MWS-2 vs 71% in MWS-1). Having a One Good Adult®(OGA) when in need was related to better mental health outcomes in young people. While the OGA was typically a parent, most often a mother for adolescents, the OGA for young adults was typically a friend or a romantic partner. There was also an increase in the proportion of young people who reported that they would talk to their family about problems, indicating the importance of family for young people.

Help-seeking in MWS-2

Talking about problems

When young people are faced with problems, 60 per cent reported that they usually talk about them with someone. Between 2012 and 2019, there has been a decrease in the proportion of adolescents who reported talking about their problems (from 66% in MWS-1 to 59% in MWS-2), however, the proportion of young adults who reported talking about their problems has not changed. Females were more likely to talk to someone about their problems than males. For adolescents, if they do talk about their problems, they are most likely to talk to their family (56%), followed by friends (36%) and other (8%). While, a different pattern was found for young adults who reported they are most likely to talk to friends (45%), followed by family (39%) and other (16%).

Talking about problems is an important factor for mental health. Those who talked about their problems had significantly better mental health and well-being compared to those who did not talk about their problems.

About one in four young people reported they would talk to no one if they had problems with feeling sad/depression (24% for adolescents versus 28% for young adults). Among adolescents, 20 per cent would talk to no one if they had problems with their family while 12 per cent would talk to no one if they had a problem with their boyfriend or girlfriend. Similar patterns were found for young adults, where 16 per cent would talk to no one if they had problems with their family, and 14 per cent would talk to no one if they had a problem with their boyfriend/girlfriend. For both adolescents and young adults, males were more likely to talk to no one (18%) about problems with their romantic partner.

Sources of support

Sources of support

Young people were most likely to identify informal sources of support (i.e., their social networks) as the places they would use to get information or support about their mental health. Of the sources of support likely to be used by adolescents, the most common were parents (68%), friends (68%), and relatives (37%).

A similar pattern was also found for young adults, where friends (63%), parents (49%) were the most common source of support identified. In terms of formal sources of support, adolescents reported that the doctor /general practitioner or GP (21%) was the most likely form of support they would use, followed by teacher or guidance counsellor (20%). While for young adults, a psychologist/counsellor/therapist (45%) was the most cited source of formal support, followed by student counselling services (44%), doctors/GPs (38%) and psychiatrist (27%).

Professional help-seeking

Young people were also asked if they had any serious problems (personal, emotional, behavioural) in the past year and whether they sought help for these problems.

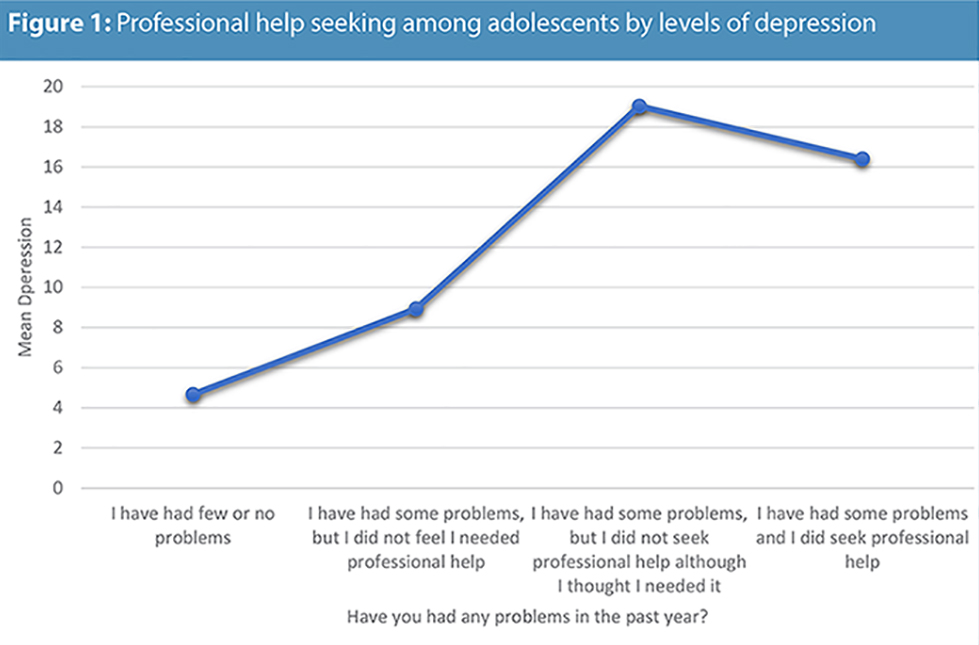

Among adolescents, more than half (54%) reported few or no problems in the past year, 31 per cent reported problems but had not felt they needed professional help, while 9 per cent reported problems but did not seek professional help even though they felt they had needed it. Six per cent reported that they had problems and had sought professional help.

Adolescents who reported that they had problems but did not seek professional help displayed significantly higher levels of depression and anxiety than all other adolescents, including adolescents who reported that they had had problems and sought professional help (See Figure 1).

A higher proportion of young adults reported having problems that needed professional help than adolescents: Some 22 per cent of young adults said they had few or no problems in the past year, 27 per cent had some problems but did not feel that they needed professional help, while 25 per cent had problems but did not seek professional help, despite feeling that they needed it. Finally, 26 per cent of young adults indicated that they had problems and had sought professional help. Similar to adolescents, those who had problems but did not seek help had significantly higher levels of depression than all other groups.

Thus, 1 in 10 adolescents and one in five young adults, feel that they have significant problems that require professional help but are not seeking help. Greater consideration of why these young people are not seeking help is needed. Research has identified key barriers to seeking help among young people include stigma, mental health literacy, specifically when to seek help, (Schnyder et al., 2020) and self-reliance (Sheppard et al., 2018), while ‘positive past experiences with help-seeking’ has been identified as a key facilitator for help-seeking (Gulliver, 2010).

Lifestyle factors related to mental health

Lifestyle factors such as sleep, social media and physical activity were a unique focus of MWS-2 that was considered in relation to mental health.

For adolescents, nearly one in two were classified as having good sleep hygiene (defined as 8-10 hours sleep per night) (US National Sleep Foundation). Females who did not get the recommended amount of sleep were more likely to be in the moderate range for anxiety. Similar patterns were observed for depression.

Poor sleep hygiene was also related to lower levels of body esteem. Adolescents who reported spending more than three hours on social media per day (36%) were likely to be in the very severe range for depression and anxiety, and displayed significantly lower levels of protective factors such as optimism, self-esteem, body esteem, and lower problem-solving based coping.

Those who spent three plus hours online were also less likely to play sports, engage in volunteer activities or hobbies and had poorer sleep quality.

International research has found a relationship between social media use and depressive symptoms in adolescents, where this relationship was stronger for females than males (Kelly et al., 2018). Greater social media use was related to poor sleep, online harassment, low self-esteem, and poor body image, and in turn these factors were related to higher depressive symptoms in adolescents. However, other research disputes the relationship between social media use and mental health outcomes (Jensen et al., 2019; Orben & Przybylski, 2019). Clearly, more research is needed to examine the effect that social media has on the lives of young people today.

For young adults, 62 per cent had good sleep hygiene (defined as 7-9 hours sleep per night) and were likely to be in the normal range for depression. A similar pattern was observed for anxiety. Those who reported good sleep were significantly higher on protective factors such as optimism, self-esteem, resilience and social support than those with poor sleep hygiene.

About one in five young adults met the World Health Organization guidelines for physical activity, defined as 150 minutes of moderate-to -vigorous activity per week.

About 12 per cent of young adults reported no physical activity which is concerning. Those who reported getting the recommended amount of physical activity were more likely to fall into the normal range for depression and anxiety than those who did not.

Clearly, the MWS-2 outlines the importance of healthy lifestyle choices in relation to mental health outcomes. Physical activity, good sleep hygiene, less time spent on social media were significantly related to better mental health outcomes. These findings are supported by other research highlighting how lifestyle factors and choices that promote psychological health and well-being are important in preventing mental conditions (Velten et al., 2014).

Better understanding

Better understanding

This research provides new insights into and a better understanding of young people’s mental health and well-being.

The research indicates that many young people still do not talk about their problems and there has not been an increase in the proportion of young people who report talking between MWS-1 and MWS-2. However, among those who report talking, they are more likely to talk to their family, highlighting the importance of family to young people.

There is still evidence of stigma, as one in four young people would talk to no one about problems with depression/feeling sad.

We also see that many young people who say that they have serious problems and need professional help are not seeking it.

These young people are displaying significantly higher levels of distress and are aware that they need professional support.

Careful consideration is needed by professionals around the barriers to young people seeking help. The role of health professionals in supporting young people`s mental health is crucial.

GPs are one of the top formal sources that young people are likely to use for information or support about their mental health.

Contact with primary healthcare among young people seeking support for their mental health presents an ideal opportunity for intervention.

Lifestyle behaviours and choices are related to mental health outcomes.

Clearly, a holistic approach to supporting a young person’s mental health is needed and attention to the elements of care of relevance to a young person’s developmental context is required, including social and recreational pursuits, to bring about mental health promotion. ![]()

References

- Dooley, B., O’ Connor, C., Fitzgerald, A. & O’Reilly, A. (2019). My World Survey: 2 – The national study of youth mental health in Ireland. Dublin: Jigsaw – The National Centre for Youth Mental Health and UCD School of Psychology.

- Dooley, B. & Fitzgerald, A. (2012). My World Survey: The national study of youth mental health in Ireland. Dublin: Headstrong – The National Centre for Youth Mental Health and UCD School of Psychology.

- Gulliver, A., Griffiths, K.M. & Christensen, H. (2010). Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 10, 113. DOI:10.1186/1471-244X-10-113.

- Jensen, M., George, M.J., Russell, M.R., & Odgers, C.L. (2019). Young adolescents’ digital technology use and mental health symptoms: Little evidence of longitudinal or daily linkages. Clinical Psychological Science, DOI: 10.1177/2167702619859336.

- Kessler, R.C., Amminger, P.A., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Lee, S., & Ustan, T.B. (2007). Age of onset of mental disorders: A review of recent literature. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 20(4), 359-364.

- Kelly, C.M., Jorm, A.F., & Wright, A. (2007). Improving mental health literacy as a strategy to facilitate early intervention for mental disorders. The Medical Journal of Australia, 18U7(S7), S26-S30. DOI: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01332.x.

- Kelly, Y., Zilanawala, A., Booler, C., & Sacker, A. (2019). Social media use and adolescent mental health: Findings from the UK Millennium cohort study. EClinicalMedicine, DOI: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2018.12.005.

- Lovibond, S.H. & Lovibond, P.F. (1995). Manual for the Depression Anxiety & Stress Scales. (2nd Ed.) Sydney: Psychology Foundation. https://www.sleepfoundation.org/.

- Mitchell, C., McMillian, B., & Hagan, T. (2017). Mental health help-seeking behaviours in young adults. British Journal of General Practice, 67(654), 8-9.

- Orben, A., & Przybylski, A.K. (2019). The association between adolescent well-being and digital technology use. Nature Human Behaviour.

DOI: 10.1038/s41562-018-0506-1. - Patel, V., Flisher, A.J., Hetrick S., & McGorry, P. (2007). Mental health of young people: a global public-health challenge. Lancet, 269(9569), 1302-1313. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60368-7.

- Schnyder, N., et al. (2020). Perceived need and barriers to adolescent mental healthcare: agreement between adolescents and their parents. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 29, e60, 1-9. DOI: 10.1017/S2045796019000568.

- Sheppard, R., Deane, F.P. & Ciarrochi, J. (2018). Unmet need for professional mental healthcare among adolescents with high psychological distress. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 52, 59-67.

- Velten, J., Lavallee, K.L., Scholten, S., Meyer, A.H., Zhang, X.C., Schneider, S., & Margraf, J. (2014). Lifestyle choices and mental health: A representative population survey. BMC Psychology, 23(2), 58. DOI: 10.1186/s40359-014-0055-y.

- World Health Organization (2011). Information sheet: global recommendations on physical activity for health 18-64 years old. https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_adults/en/.

- Ystgaard, M., et al. (2009). Deliberate self-harm in adolescents: Comparison between those who receive help following self-harm and those who do not. Journal of Adolescence, 32(5), 875-891. DOI:10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.10.010.

Associate Professor Amanda Fitzgerald is a lecturer in University College Dublin School of Psychology. The core team members of the My World Survey include Prof Barbara Dooley, Dr Aileen O Reilly and Dr Cliodhna O’Connor. More details on the study can be found at: www.myworldsurvey.ie.